Over the past year, I have experimented with different methods of home automation, from scripts that automatically render my projects for me, to light control. In this time, I have been using an old E-machines desktop computer with a failing hard disk and limited RAM. Well, this holiday season, the thing finally gave out on me, but luckily I had a spare Raspberry Pi to fill this void. I transferred the necessary scripts that I had written, as well as the necessary programs that I had found online and compiled. The current system has my Pi mounted to a wall on one end of my room with a status monitor, connected to a very long USB cable which snakes around the perimeter of my room to the opposite wall. There, the USB cable is connected to a USB hub which connects to a USB-DMX dongle (to control RGB lights), and a USB relay module to control a tower light and buzzer set for special alert cases. The whole thing is controlled by a script that checks a Google Firebase database every 5 seconds for changes. I have created an Android app using MIT App Inventor which communicates with the same Firebase database, thereby communicating with the Raspberry Pi over the internet. With this setup, I can change the color of my room lights, tell the Raspberry Pi to say a specific phrase, and more. To date, my home automation system is equipped with the following abilities:

- A briefing program, which uses Linux’s “espeak” text to speech terminal program to address me and give me updates on the status of various processes. For this program, the script first gathers various statistics by loading up various web pages, saving them into text documents, and parsing them. For example, the briefing program provides the weather, temperature, the number of followers on each of my social media accounts, as well as more personalized data such as the number of files rendered over night.

- A continuous social media checker, which alerts me when I gain or loose a follower on Instagram by telling me verbally and by turning the LEDs in my room either green or red.

- Full LED lighting control via a USB-DMX interface, and a strip of RGB LEDs connected to a DMX decoder.

- A facial recognition program that uses a webcam connected to the Pi, complete with a full login and logout system, which can recognize a person entering the room and identify them, setting the room state to their preference.

- A custom phrase repeater, which gets its phrase from the Android app.

- A custom alarm clock which will read input from my app, setting an alarm for the appropriate time and waking up the room occupant at the appropriate time using voice features.

- And much more!

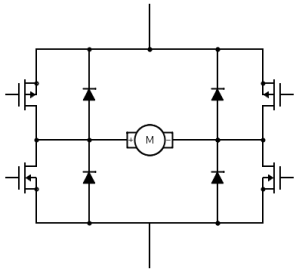

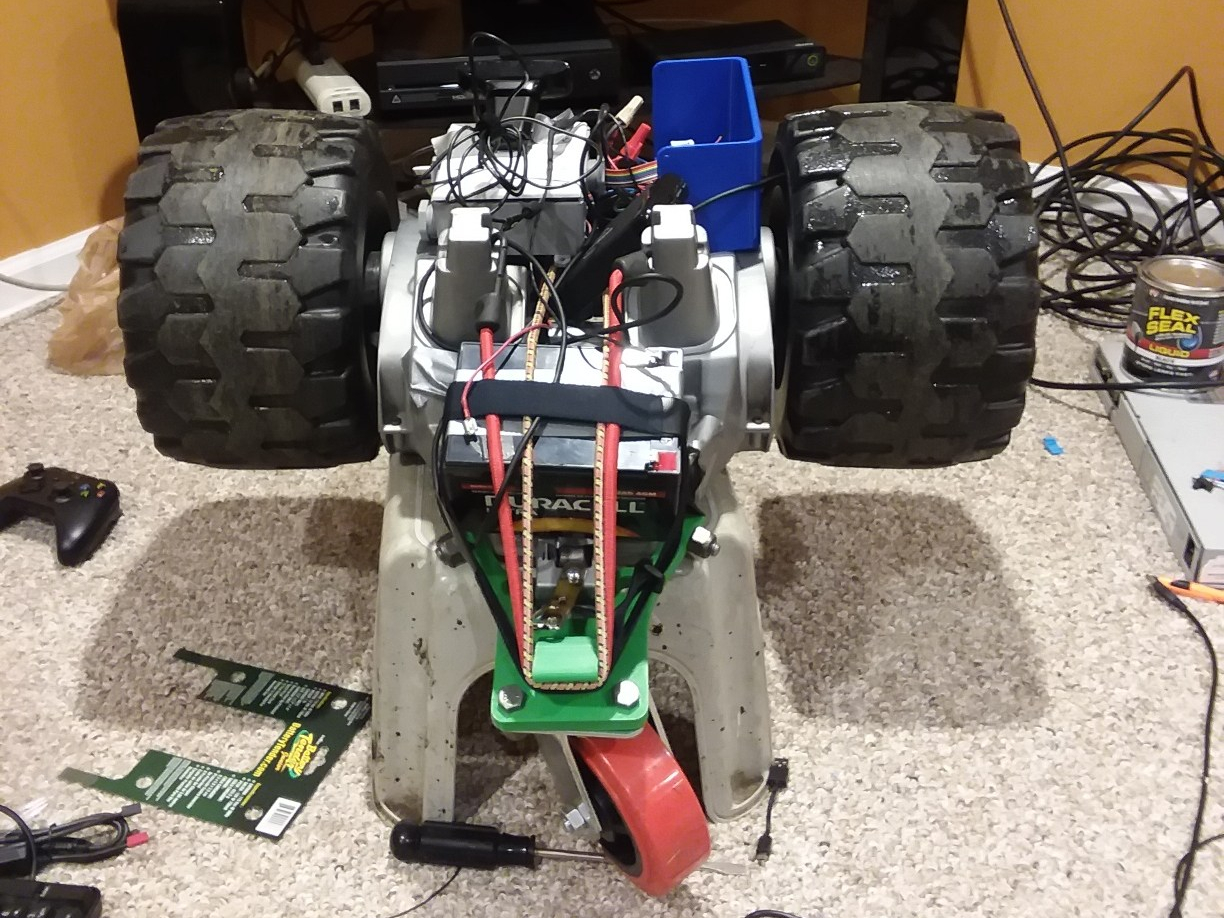

As I mentioned above, the two main complex connections involved with this setup are the USB relay module, and the USB-DMX interface. I managed to find open source command line programs for Linux online to control both the USB relay module and the USB-DMX interface. Just pure luck! Below are images of both interfaces.

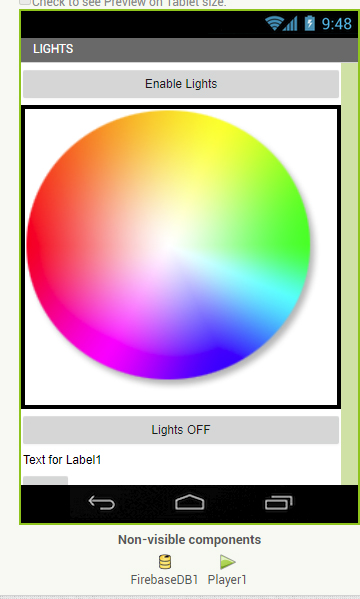

Above, you can see a screenshot from the light controller portion of my app, and some of the lighting options.

This has been a very, very brief overview of the system. Parts of it, such as the facial recognition system and the relay control, took many days to set up and get working properly. If you would like to know more, leave a comment requesting a future blog topic!