Recently, I had the opportunity to produce a CGI/visual effects-based music video for AdhesiveWombat, an electronic music creator on SoundCloud, YouTube and the like. If you’re into tech, you may even know him as the producer of the “theme song” for Linus Tech Tips’s “WAN Show“. Well, that “theme song”, AKA “Storm Crusher”, got an animated, VFX music video addition this summer! Using a suite of 3D software and compositing tools, I put together a VFX adventure for this track with the help of some live action footage, photorealistic raytracing, and particle simulations! If you haven’t see it yet, check it out!

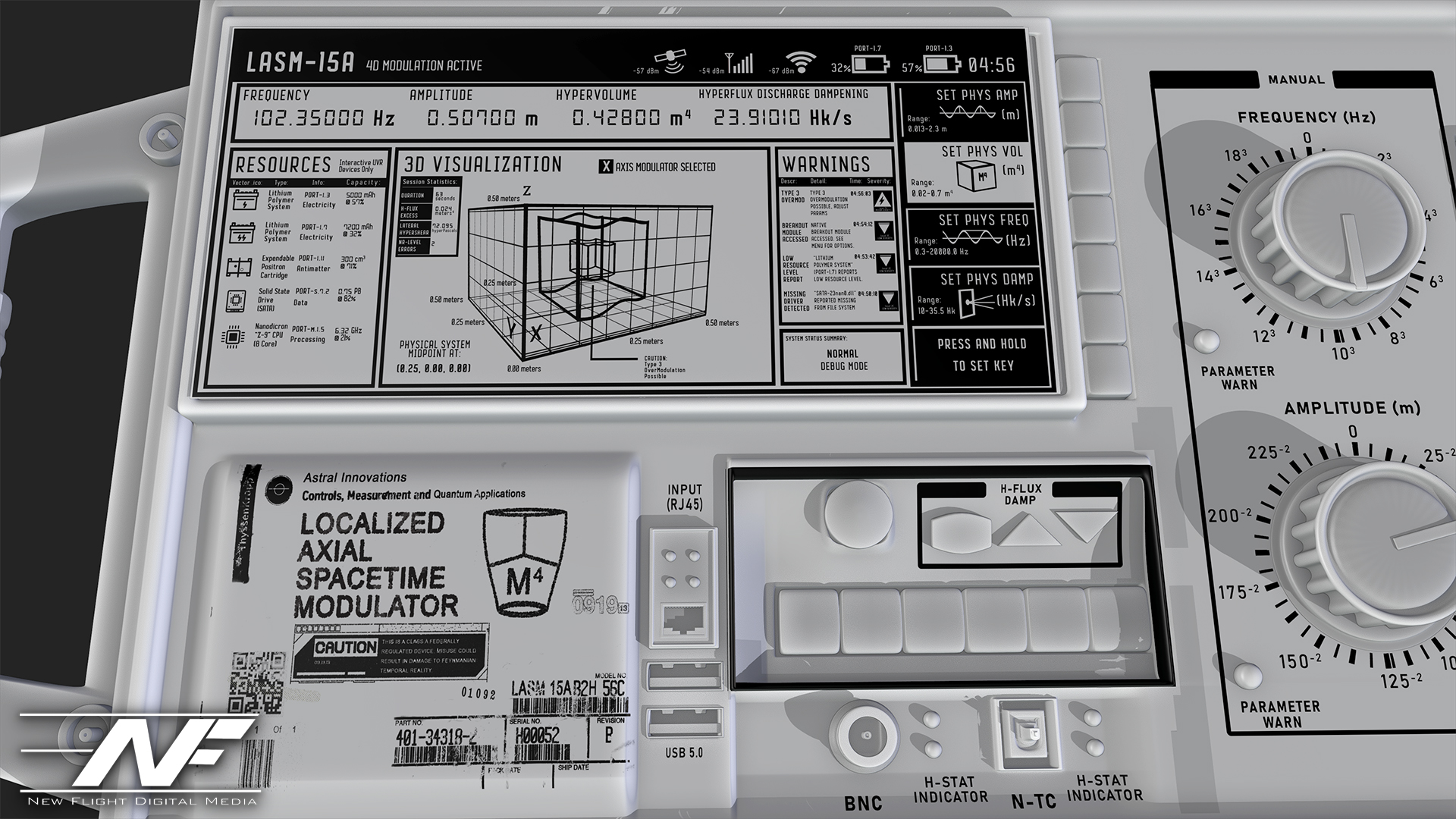

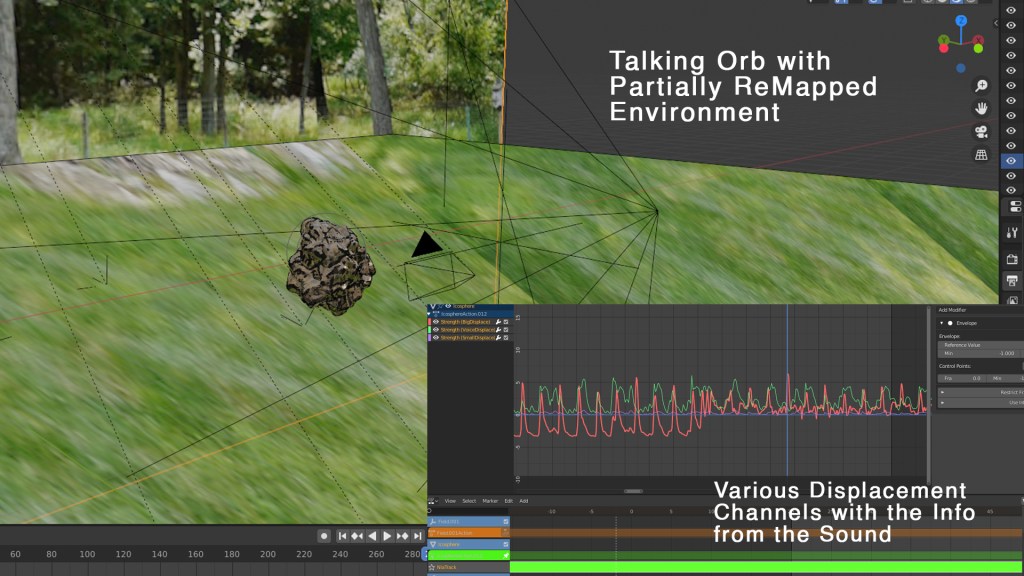

This video involved many production and post production processes, but I’d like to highlight a few. For this video to work, you’ll notice that the music needed to “drive” the animation in some parts. I used a script to convert certain frequencies from the sound track (typically between 0 and 4 KHz), into usable animation data that could be manicured, amplified, and turned into pulsations, movement, and force field data for particle animations.

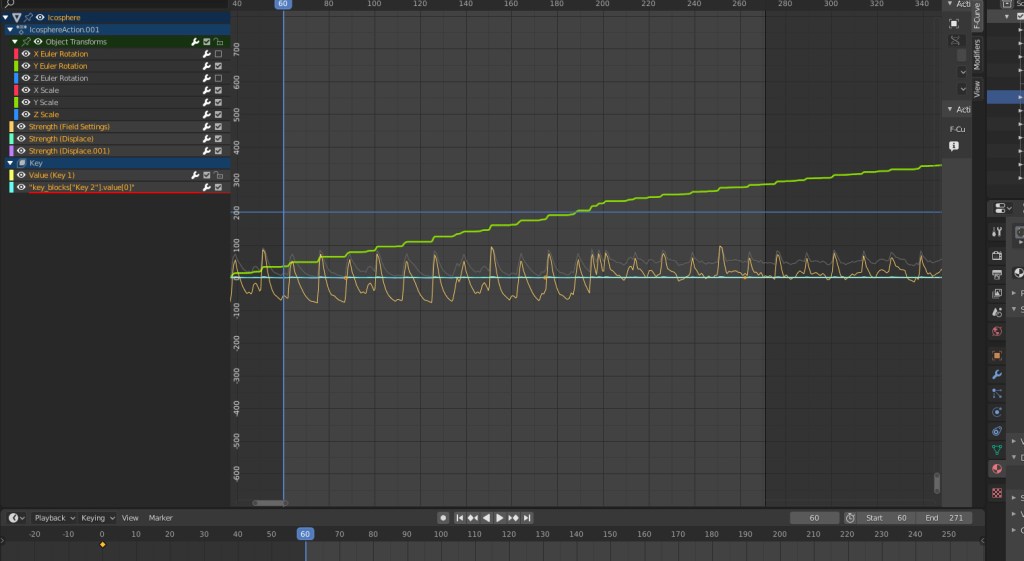

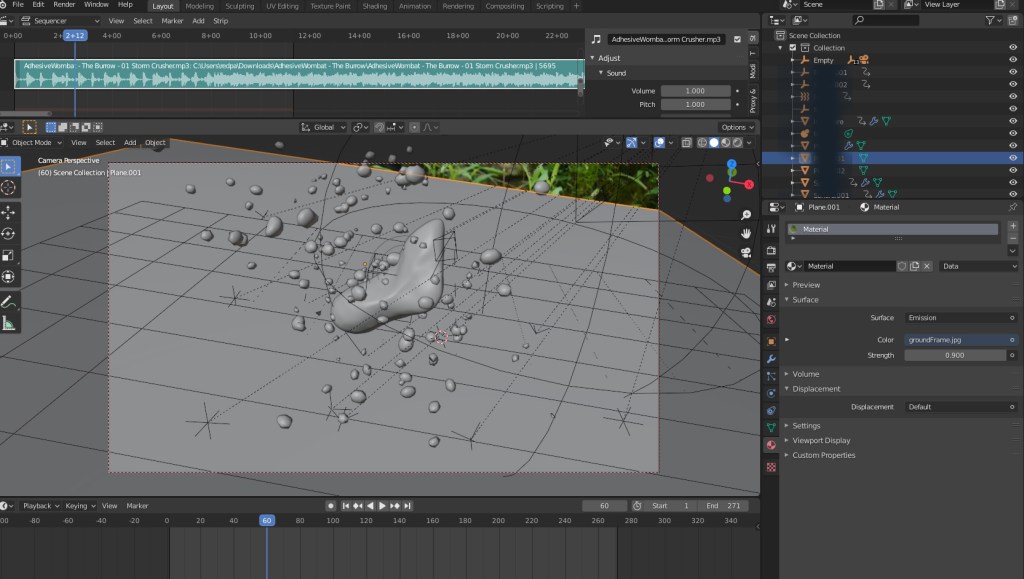

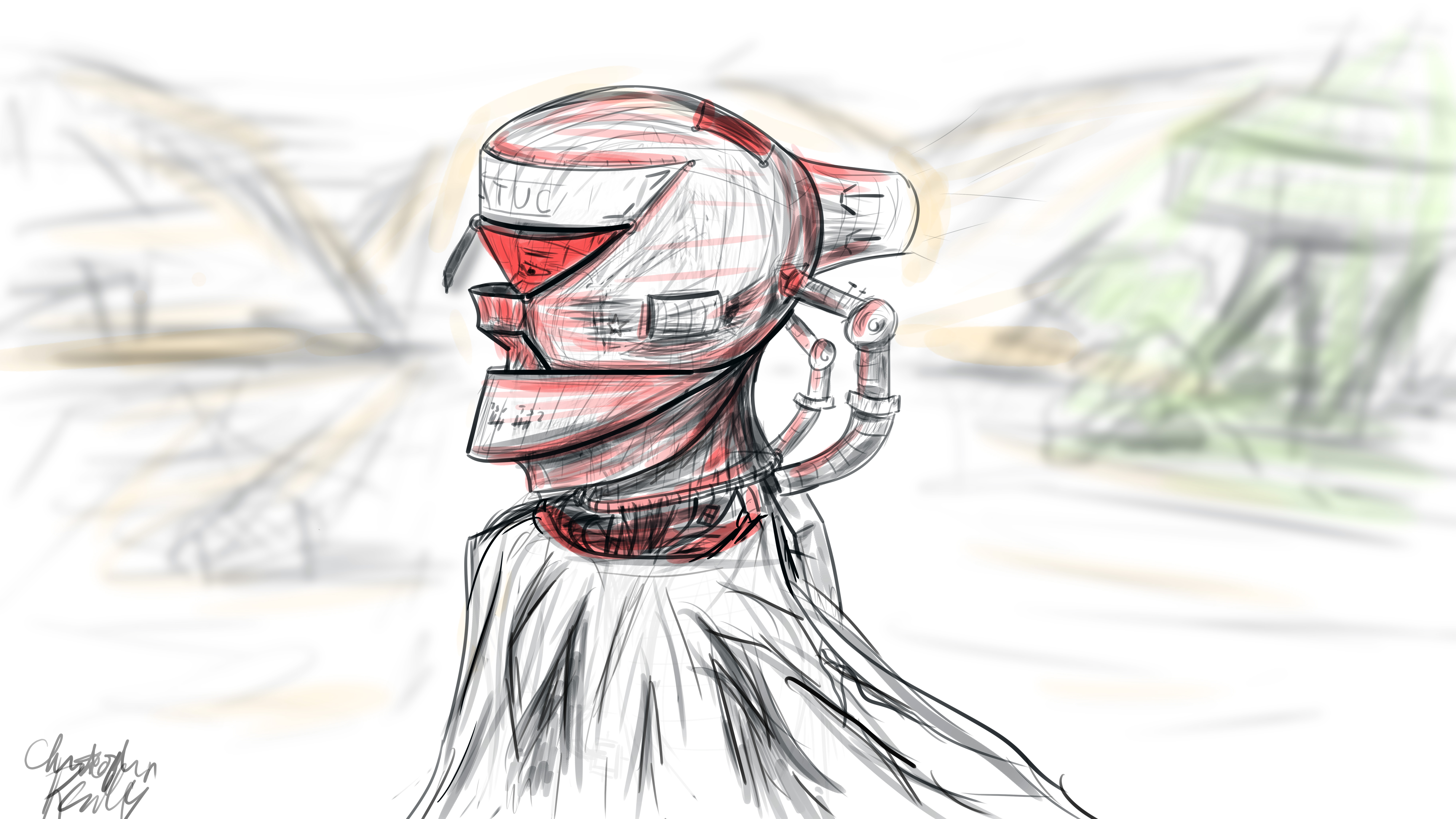

Here, you can see the pulsating orb and its particles from the beginning, alongside a graph visualization displaying several parameters driven by the sound from the music. You’ll also notice the music track along the top of the viewport… super useful when you want to match the movements up just right! Here’s another example of the orb, along with its graph view (showing several channels of displacement data driven by sound):

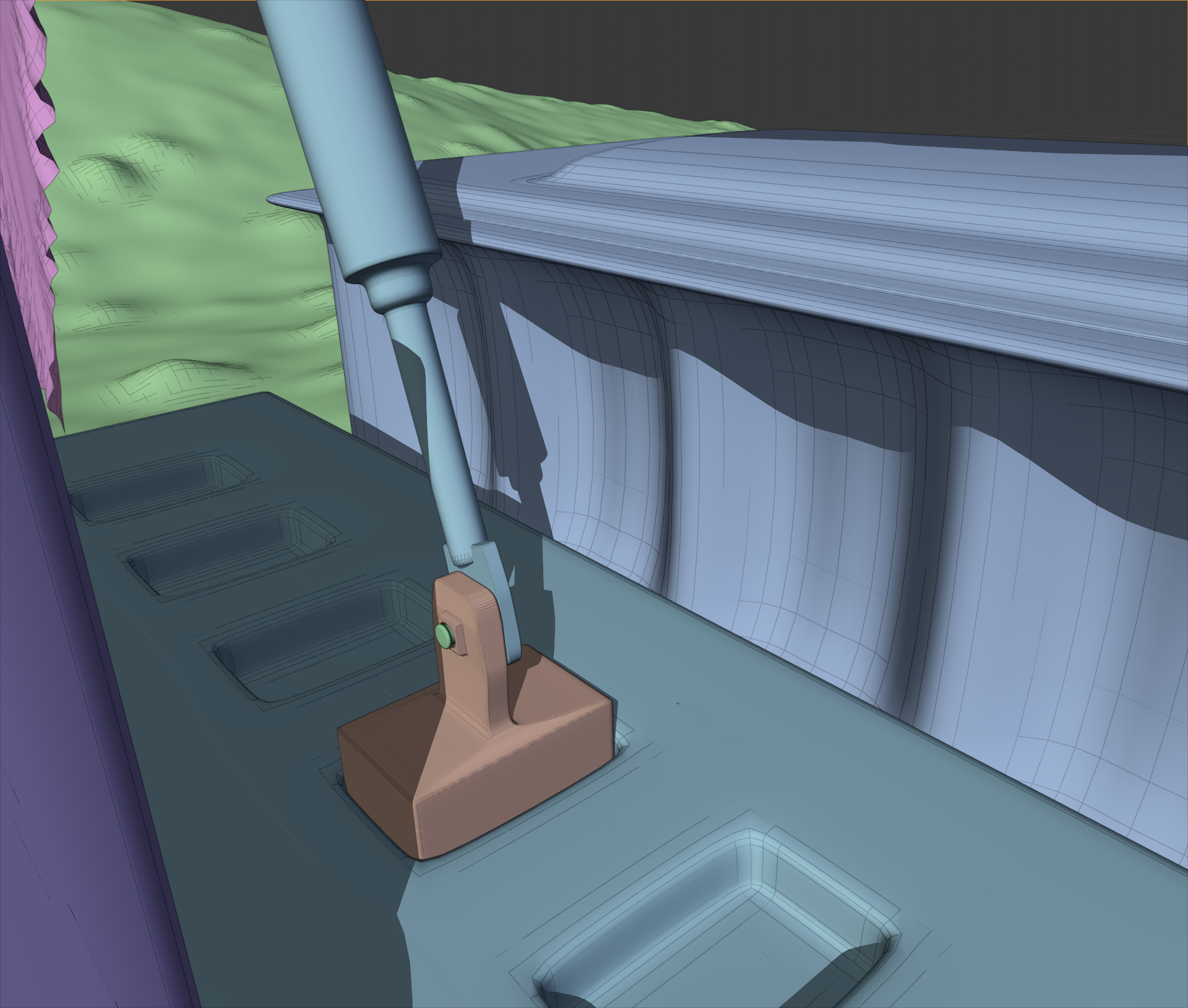

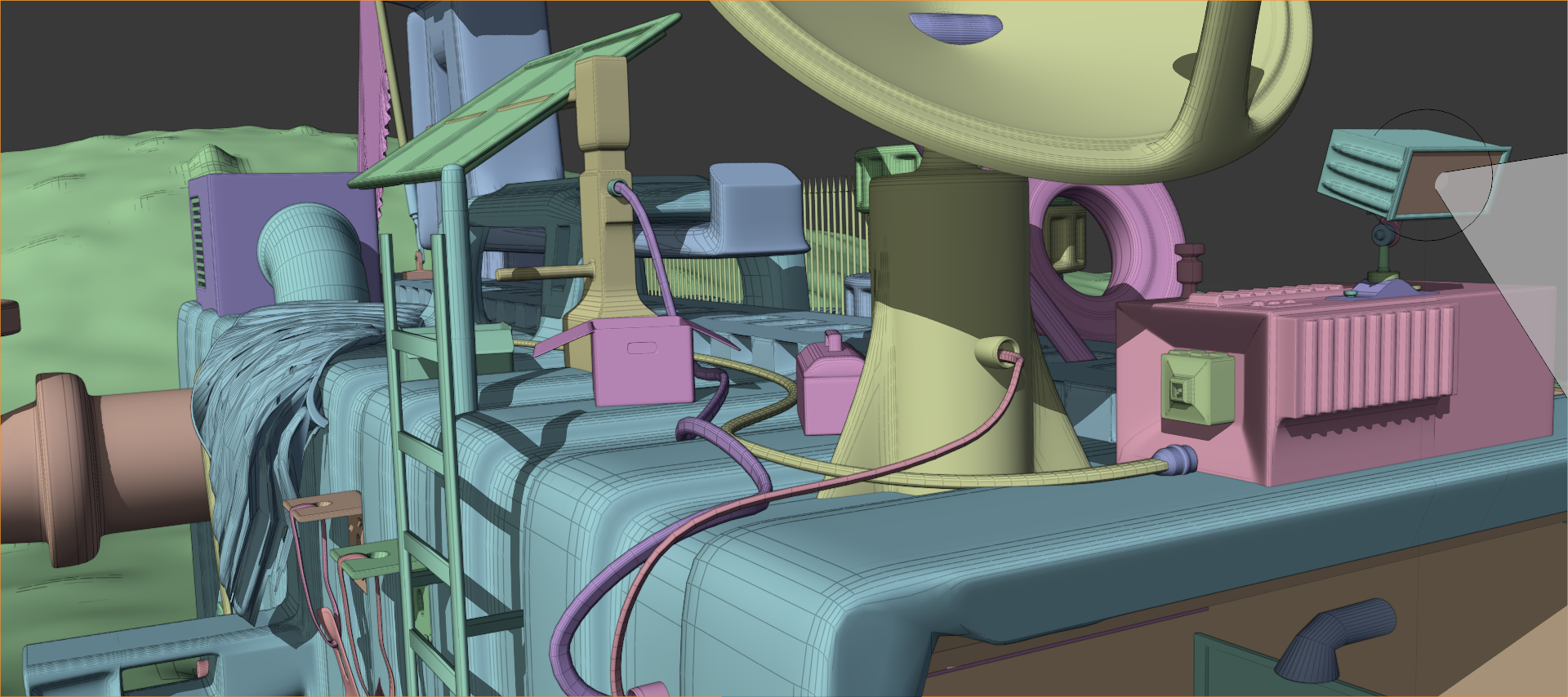

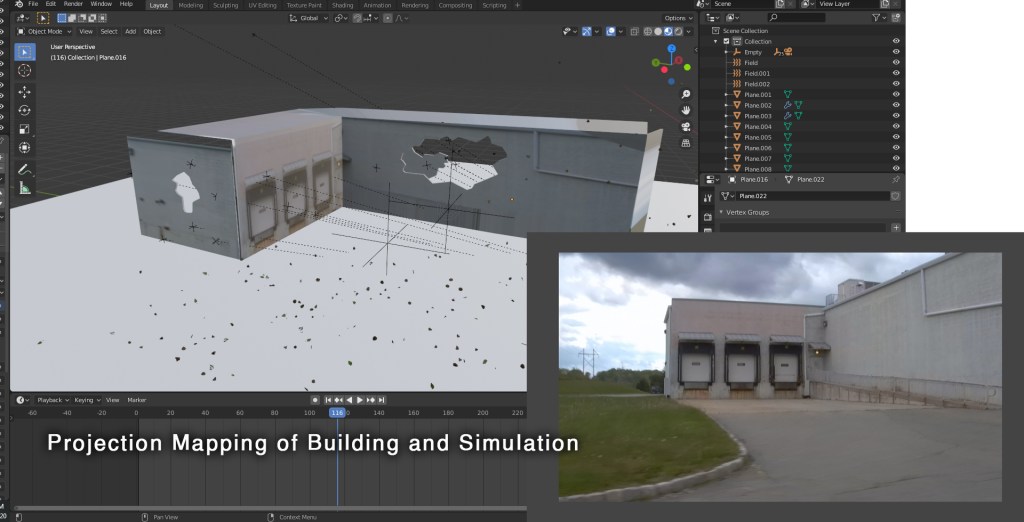

To complete this video, I needed to use “projection mapping”. That is, I needed to partially reconstruct some environments in 3D, and project imagery onto them in order to ensure that the 3D objects in the scene would conform to the lighting situation when the video was shot. Here’s an example of partially re-projecting a building onto a rough box model:

This allows for so many possibilities. Water, for example (of which there is a lot in this video), has a refractive index (the extent to which light is bent when it passes through the object). This means that material needs to be present behind the object so that there is something to “see” through the water when the light gets bent through it. Using this technique, I can recreate real world lighting conditions (with the help of an HDRI backdrop).

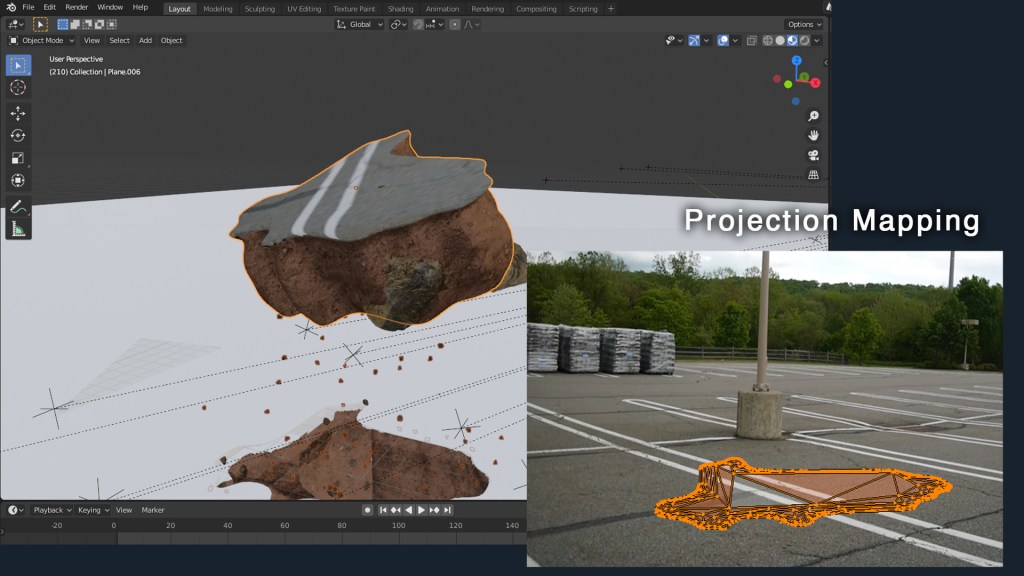

Here, you can see how this is accomplished… a mesh’s geometry is “projected” from the tracked camera’s point of view, and the imagery in that scene is applied. This allows me to make actual “chunks” of the parking lot rip apart!

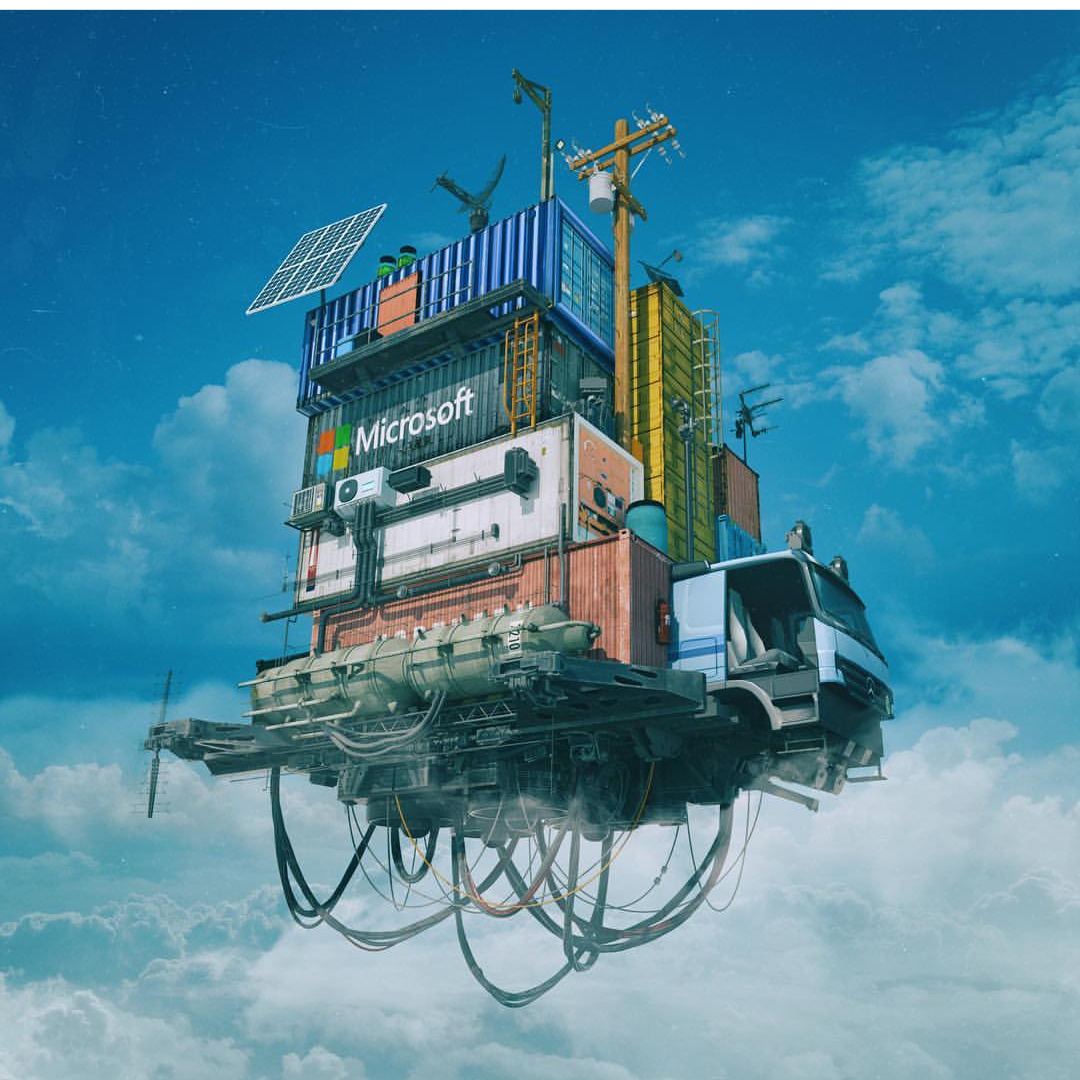

Finally, I’d like to discuss those clouds. The clouds were produced procedurally using dynamic noise mixed with a black/white 3D mask to “guide” the clouds to where they needed to appear (the mask was animated to “steer” the clouds to different areas). You can see how the clouds only appear in a small area, although the mesh is much larger:

These clouds used volumetric materials, meaning that what you see is a subset of the mesh’s volume, rather than its surface. Raytracing render engines are needed to accomplish this, since the light bounces (the paths that the light takes) through the clouds need to be calculated by the computer. Using this technique, you can also get some really crisp volumetric shadows from other objects in the scene, like in the one above, for example. When that chunk of dirt comes out of the field, the crisp shadow edges on the volumetrics certainly help “sell” the effect.

Overall, this was such a blast! I’m glad everyone seems to like the results. Super, super special thanks to AdhesiveWombat for allowing me to bring his already legendary music a visual counterpart. Please go follow him, etc:

AdhesiveWombat’s Socials:

New Flight Digital’s Socials:

Want to get in touch? Visit newflightdigital.com!